CLASS WAR

2020 is the 50th anniversary of the founding of Verso Books. In that time we have published books that have become classics of the left. We also published Class War's A Decade of Disorder. Here, Colin Robinson, former editor at Verso, recounts the events leading up to its publication – and the subsequent fire-bombing of the Verso offices in retaliation.

The late 1980s was an arid time in Britain for anyone interested in politics on the left. Since the defeat of the miners in the brutal year-long strike of 1984-5, pretty well any organized opposition to Margaret Thatcher’s granite faced admonitions had headed for the hills. Not only was there no alternative, there wasn’t even such a thing as society in which the seeds of one could grow. Dissident political intervention had been reduced to little more than exasperated harrumphs and sharply intoned cursing.

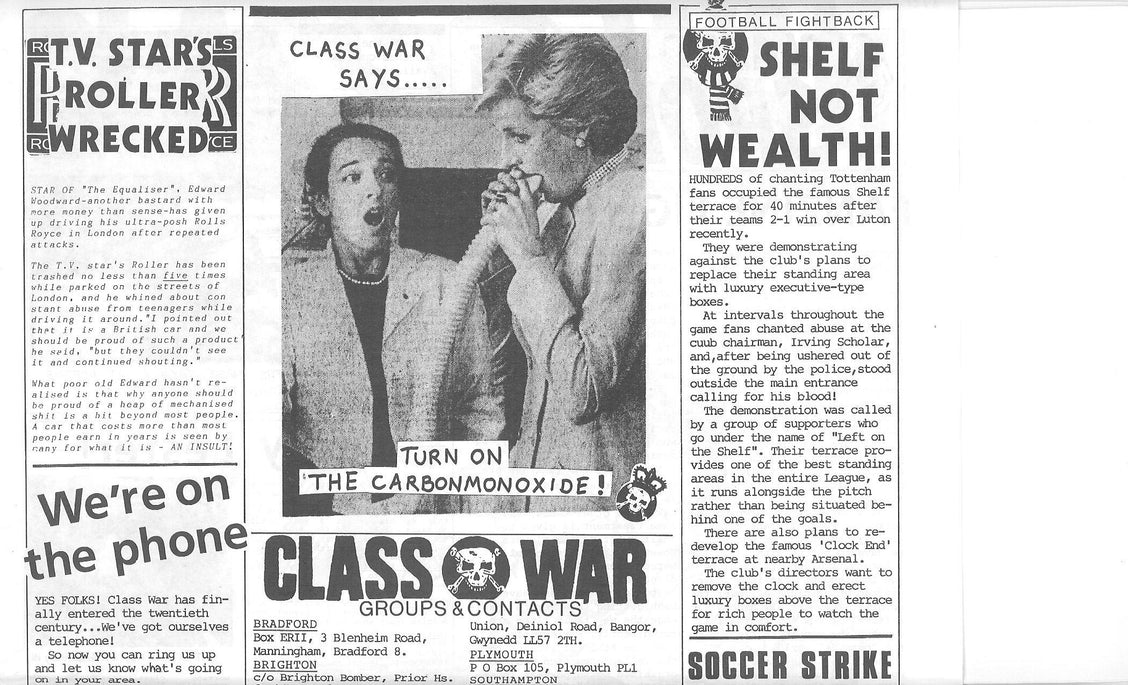

When it came to the business of shaping and hurling insults, especially those designed to offend with their loutishness and perfidy, one organization repeatedly took the Prix Goncourt. Class War was a rowdy group of anarchists, no more than a few hundred strong, that had built a reputation disproportionate to its size by raising invective to unprecedented levels of stridency and delivering it with the flat fisted thump of the tabloids. Their magazine, which took the name of its sponsoring organization, combined screaming headlines and crude production standards to savage the Tory government, the royals, and the rich, as well as anyone in the middle-class who believed the Labour Party could deliver Britain’s “septic isle” from their baleful rule. The magazine greeted the birth of Charles and Di’s first born by reproducing a widely published photograph of Harry in his proud mother’s arms outside Charing Cross hospital under the screaming legend “Another Fucking Royal Scrounger.” A subsequent cover featured a photograph of a graveyard, with tombstones stretching to the horizon, above the banner “We Have Found New Homes for the Rich”. And the oleaginous visage of Neil Kinnock, then leader of the Labour Party, appeared under an economical strapline in crude 60-point type: “WANKER!”

It occurred to me that it might be a good idea to collect together the best of Class War’s splenetics in a book. I had no illusions that the sallow-faced, shaven-headed congregants wiping curry sauce off their thin T shirts in front of the nation’s chippies would be lining up to buy. No, it was amongst the Conran/IKEA left, who had seen their pet causes - the Anti-Nazi League, the National Abortion Campaign, the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament - disappear with a swirl of blue foam in the toilet bowl of Thatcherism that I thought the book might find a response. They had nothing left but their vitriol.

Getting hold of Class War proved less than straightforward. A box number address appeared in the back of the newspaper on a form for would-be members and I duly sent off a letter to it, inquiring if they might be interested in anthologizing the best of their work. No reply. It wasn’t easy to get the phone number or address of any of the members in the group from my usual range of contacts around the left. Partly because they despised what they saw as the middle-class tokenism of the campaigns and socialist organizations, and partly because they were not keen for the police to know of their whereabouts, Class War kept themselves to themselves. Then, about two months after I had sent my initial letter, I got a phone call from a man in Bristol with the pleasingly redolent name of Ian Bone

“Are you Colin Robinson?” The inquiry was guarded and delivered in a thick cockney accent. I owned that I was. “Well about this book, tell us, what was you thinking of?” I explained my idea for a collection, in words and pictures, of the best of the newspaper. He and his colleagues could write an introduction if they liked. I felt a bit self-conscious describing Bone’s associates as “colleagues”, as though they were members of a professional association, but I didn’t dare risk “comrades” given Class War’s widely expressed and withering scorn for the pretensions of the organized left. I added that we would consult with them closely on what was to be included. “I’m going to have to talk about this with the rest of the lads” Bone replied, sounding less than convinced. “I know some of them feel that, if we’re going do this, we should do it ourselves. See, the thing is, not to be rude or anything, a lot of people think you’re just a bunch of middle-class tossers.”

***

Two weeks later, on the top floor of the elegant central London offices of our publishing house, I met up with Bone and an associate of his called Tim Scargill, a large, callow-faced man with a mop of ginger hair. Upon being introduced I commented on his infamous surname and he confirmed that he was indeed related to the great miners’ leader, Arthur. Bone was looking contemptuously around the cornices and didoes picked out delicately in white against the duck egg walls of the Queen Anne room in which we sat and I immediately wished I had arranged the meeting outside the offices in some suitably grubby local pub. Evidently the senior partner of the two, Bone took the lead in the discussion. In his late thirties, he was a spry, athletic man with what little hair he had left razored close to his skull. He wore rimless spectacles that magnified sharp, darting eyes, the sort that never missed a trick, especially those pulled by poncey publishing types.

This was to be the first of perhaps half a dozen meetings that Bone, Scargill and I held, sometimes accompanied by the edgiest designer I could find, a suitably sardonic lecturer at the Royal College of Art who had been responsible for the beautiful jazz magazine, Wire. Bone proved to be an adept and generally reliable judge of what, from the often-uneven content of Class War, might stand the test of time. For my part, it was hard to draw a line when it came to determining what of Class War’s lurid and scatological output was beyond the pale for a reputable publishing house. The whole point of the group was to shock, to split open the veneer of mealy-mouthed exchanges that passed for political discourse in the repressed and servile culture that England had made its own under Thatcher. I could laugh along with the accounts of days out at the upper-class Henley regatta where Class Warriors had manned bridges to bay at and spit on the toffs in the punts below. Even the photo sequence of spiky haired, gap toothed yobs hiding in shop doorways and chucking shit filled condoms at unfortunate passing yuppies seemed more amusing, in a puerile sort of way, than dangerous.

But there were items that Bone insisted we include that gave more pause for thought. One was an exhortation that budding anarchists should kidnap the children of the rich and deposit them in cesspools at the local sewer works. Like much of Class War it wasn’t easy to determine here whether the tongue was in the cheek or clenched determinedly between the teeth. Still more difficult was the selection of photographs from what Class War called its “Page Three,” a scabrous tribute to the topless girlie pictures on which Murdoch had built the soaring circulation of his Sun newspaper. Appealing to prurience of a quite different stripe, Class War’s pin ups were of policemen in various states of distress and injury resulting from being assaulted on violent demonstrations. Under the rubric “Hospitalized Copper,” Bone suggested we include a double page spread of these grainy photographs, including depictions of officers with blood pouring from under their helmets or being stretchered away to waiting ambulances. It seemed superfluous to point out that this was likely to attract extreme displeasure from the authorities, with hazardous consequences for the publishing house, but I pleaded the point anyway. Bone, with characteristic insouciance, was unmoved.

I also had considerable concern about a cartoon strip that Bone wanted to use to accompany his introduction to the book. This featured the well-known cartoon character, Tin Tin, originally drawn by the Belgian artists Hergé. In the samizdat version proposed by Bone the central character was far removed from the loveable teenager who, with his pooch Scottie, travels across the world to rescue the Professor from the clutches of the terrible Yeti in Nepal. Here, Tin Tin had morphed into a psychotic class warrior who enthusiastically trashes a local yuppie bar, screaming exhortations to commence the revolution. I was worried that the Hergé estate, notoriously conservative, would take legal action to protect its copyright and reputation. Bone’s suggestion that we could circumvent any difficulties by removing the eponymous hero’s trademark quiff hardly seemed up to the task.

But in the end, a combination of Bone’s persistence and my inability to control him prevailed. I frequently wished I had not embarked on the project at all. Admonitions from friends that it would be the end of my publishing career, that lawyers would descend like crows on a newly ploughed field, even that prison beckoned, weighed heavily during those intense days in the autumn of 1991. I tried to dispel such anxieties by grandly recalling previous brave stands taken by publishers like Barney Rosset at Grove Press, who surmounted the prudish culture of 1950s America to allow Henry Miller to see the light of day, or Lawrence Ferlinghetti at City Lights, who had defied the authorities in publishing Allen Ginsberg’s Howl. But these publishers were defending works of literature, planting their standard for the right of significant artists to self-expression. To define the Class War anthology as “art” stretched things over a considerable distance. It barely qualified as a book.

***

[book-strip index="1" style="buy"]It was difficult to tell from which direction the deadliest fire aimed at Decade of Disorder, the title Bone picked for the anthology, would arrive. Clearly policemen’s dining halls were unlikely to be resonating to chuckles at the scintillating wit of “Hospitalized Copper”, and it was improbable that the Tory government would appreciate the less-than-delicate irony of pages headlined “You Rich Bastard – We’re Going to Get You!” Fascists, with whom Class War had recently engaged in various bloody street battles in the East End of London, seemed certain to regard the book’s publication as an irresistible provocation. But there were problems closer to home too. The Verso shareholders were far from convinced that 160 pages of crude vitriol against the rich added much to the refined left theory on which they had traditionally set out their stall. It seemed more than possible that Class War, should they decided to descend in Valkyrie fashion on the affluent squares of Canonbury or Victoria where the Verso directors lived, would fail to distinguish between the homes of the forces of reaction and those of the gauche caviar. Worst of all, the hardline faction of Class War itself, whose pathological violence was starkly evident in contributions (that I had managed to exclude from the book) on the glories of execution and castration in the cause of revolutionary justice, could easily show up at Verso to express their displeasure at the group’s dalliance with yuppie publishing. The consequences of that didn’t bear thinking about.

Getting the book printed was not straightforward either. With characteristic hesitancy in the face of a difficult choice, I had decided to seek legal advice about the book only after it had gone for plate-making at the printer. Having read the advance copy I sent to him, the company’s lawyer demurred from putting any legal advice at all in writing. But, over the phone and with an anxious insistence that was a striking departure from his normally unruffled Oxbridge mien, he made clear that publishing at all was, in his view, a serious error, that he couldn’t see the point of it, that it put the company at significant risk for very little likely gain. More specifically, he informed me that several sentences in the book, including a particularly lurid expiation on the business practices of Virgin boss Richard Branson, were highly likely to attract legal action. I called Bone to discuss the problem. His response was predictable. “Oh, come on Colin” he sneered, speaking from Bristol, “What are you, a man or a bleeding mouse? It’ll be fine, take it from me.” I explained that taking it on his behalf was more what I was worried about: I had a publishing company to protect. “Don’t go all sappy on us now” was his only retort. Clearly, I wasn’t going to get authorial approval for any last-minute deletions.

And there was another problem: changes at the plate stage of the printing process were very expensive and I wrestled with my stupidity at not bringing in the lawyer at an earlier stage. But then an original solution to the problem occurred. The overall design of the book, for reasons both aesthetic and convenient, replicated the homemade spontaneity of Class War’s newspaper. Pictures had been re-screened without concern for moiré, text was set in a rough, sub-Private Eye fashion. Without having to worry about typographical elegance, it dawned on me that I could simply score through the offending passages on the printer’s plates, leaving black lines to cover text that was unacceptable and writing “censored” by hand in the adjoining margin. Two day later I was on the train to the printers in Wiltshire. The MD of the printing company had been nervous about handling the job from the beginning and had insisted I sign a waiver that any legal consequences would be borne by the publisher alone, something I had yet to tell the Verso shareholders. But his staff were friendly enough and made me cups of tea as I sat with a broad-nibbed pen removing Branson and a few other likely litigants identified by our lawyer from the book’s pages. The result was pleasingly homespun and subversive. Returning to London that afternoon, I felt a weight had been lifted.

A few weeks later, in mid-November, finished copies of the book arrived at the Verso offices. At the top of the unlaminated cover, the title was picked out in crude red type and straddled a picture of a smoke wreathed Trafalgar Square during a pitched battle between police and poll tax protestors. Most of the staff around the office agreed the book looked promising but, I couldn’t help notice, not in a voice loud enough to be heard by anyone else. I also noticed that, on some copies, the plate on the printers’ press had shifted slightly so that the black lines that I had carefully drawn to hide offending text had slipped down fractionally. Rather than obscuring the most legally sensitive sections of the book, they now underlined them.

We decided to forgo a publication party. Bone was concerned about uninvited guests who might show up; I was concerned about those who would be invited. The launch was instead marked by an appearance of Bone and Scargill on Channel 4 television’s popular Jonathan Ross show. Ross, much less the unreflective, good-time lad than he would have the world believe, had been in contact with Bone on a previous occasion. He needed edgy material capable of keeping awake a Friday-evening audience that had been thrown out of London’s pubs at 11 o’clock, just as it was every other night under Britain’s absurdly archaic licensing laws.

I didn’t accompany Class War to the studios. Judging by subsequent reports this tuned out to be a sensible choice. Before going on air, Bone and Scargill attempted to start a fight with the other guests in the Green Room and security staff were summoned. On the show itself, Bone’s sneering loutishness seldom rose above a thin bravado, but it was certainly unlike most primetime television. Afterwards it was off to a wine bar in Charlotte Street where a further attempt at provoking a fight, this time with both customers and staff, led to the arrest and temporary detainment of my authors and a number of their friends in the Warren Street police cells. I knew Bone well enough by now to recognize this was not the arbitrary violence of an uncontrollable psychopath, though perhaps having a few of that sort around helped the cause. No, it was on the media, always open for stories about violence among the lower orders, that Bone had set his sights.

But on this occasion, they didn’t bite. The events of publication night were widely ignored. This mattered less because plenty of other things were happening around the book. The Guardian newspaper devoted considerable space to discussing the way it “tested the limits of tolerance of a liberal society” and reported that moves were afoot to have the matter discussed in the House of Commons. A spokesman for the Metropolitan Police Force appeared on television and railed against the disgraceful irresponsibility of releasing such a scabrous publication. Wagging an accusing finger at the camera he averred that “Someone, somewhere, is making a great deal of money out of this and I think we should know who it is.” I would like to have known myself.

***

[book-strip index="2" style="display"]It was a freezing November morning, a couple of months after the publication of A Decade of Disorder. I wasn’t sleeping well because of stress and had arrived at the Verso office early. Huffing clouds of steam into the icy air as I searched through my pockets for a key, I noticed an unusual smell around the doorway. It was only on entering the hall that I realized it was kerosene, which evidently had been poured through the letterbox and then ignited. The carpet inside, a rich grey lamb’s wool, was now extensively singed; the pale green wood paneling on the walls had blackened and blistered up to waist height. Someone had evidently tried to set the place alight. It wasn’t hard to connect this near-disaster to Class War.

I stood in the doorway for a minute or two, scratching at the crisp bubbles of paint on the wall, wondering what to do. Calling the police seemed the most obvious course of action. But the idea of inviting police into a building that had been attacked for publishing a book that their Commissioner had already fiercely denounced was not especially appealing. I went upstairs, sat at my desk, and stared disconsolately out of the window.

It was perhaps half an hour later that Claudia, the production assistant who doubled as receptionist arrived. I’d noticed that Claudia generally arrived at work on time, unlike anyone else. I‘d come to appreciate that about her. Now she burst into the room with an alarmed look on her face “Jesus, what happened downstairs?” she asked, pointing back through the door to emphasize the urgency of the question.

Claudia was only 21 and certainly too young to bear the burden of responsibility I was about to place on her slender shoulders. But weighed down with fear and enervation by the entire business, I had no choice. “I think someone tried to set the building on fire” I said flatly. “It’s probably because of the Class War book. I don’t know what to do.”

Claudia looked at me with an expression somewhere between contempt and pity. “Well it’s obvious,” she said firmly, “we have to call the police. I’ll do it.” She left for her desk in the room next door.

Twenty minutes later two policemen arrived. Claudia did most of the talking. Yes, we both thought it was a deliberate attack on the building. No, we had no idea who might be responsible. The officers were solicitous without seeming greatly concerned. My paranoia interpreted this as evidence that they had already connected the incident to “Hospitalized Copper.” They sauntered out without even examining the crime scene.

I pointed this out to Claudia, alongside my suspicions that political motives lay behind their indifference. She was unconvinced. “They’re Soho cops. There’s gang wars going on all over this part of town. I bet they see it all the time.” I now recalled that the building had only just survived a major fire soon after Perry Anderson had bought it. Claudia’s matter-of-factness calmed me down. I appreciated that about her too.

Robin Blackburn arrived perhaps an hour later. I heard him greeting Claudia as he passed her open door, surprisingly not stopping as he headed up to the New Left Review office on the third floor. I went up to see him. He was barely visible behind the enormous piles of paper and books that had accumulated on and around his desk.

“We called the police” I said “They seemed pretty disinterested.”

A voice issued from behind a teetering ziggurat dedicated to the study of Perestroika. “Why?” it said.

“I don’t know” I replied “they just didn’t seem bothered.”

“But why did you call them?” the voice inquired

“Because of the fire in the hallway downstairs” I said

“There’s been a fire downstairs?” The voice was incredulous.

A mane of white rose slowly above the stacks followed by a face, smooth and handsome, and evidently confused. “I should take a look” he said, “show me where it is.”

That Robin, on entering the building, could have failed to notice that it had come close to ashes as a result of an arson attack was, on reflection, less surprising than the attack itself. I added Robin to the list, headed by Claudia, of people who made me feel calmer about the world.

***

By December it was clear that sales of A Decade of Disorder were not breaking through in the way that I hoped they might. The general public perhaps felt that the extensive coverage of the book’s publication was as much as they needed to know about it. My pal Ramsay at AK Press, an anarchist distributor and publisher with offices in Edinburgh and San Francisco, sold the book effectively into the indie record shops and the few remaining left bookstores in the UK. But, notwithstanding the brave decision of Waterstones on Charing Cross Road to create a corner window display that included photographs of the street outside being looted and burned in a recent poll tax demonstration, the mainstream outlets broadly ignored the book.

Some months after publication, Iain Sinclair’s review of A Decade of Disorder dominated the front cover of the London Review of Books and filled several subsequent pages, a word count rivaling that of the book itself. Its prominence seemed at odds with Sinclair’s assertion that Verso had “provided a dubious service” in publishing the anthology, words which only deepened my gloom about an experience I was already wishing had belonged to someone else. Though it bridled, there was sense in Sinclair’s argument. Class War was finding it increasingly hard to bring together the young, desperate people who had seen their teen years wrecked by Thatcher and who had fought so bravely in the poll tax demonstrations. Without the breath of air these youngsters provided, the magazine increasingly became a parody of its former self, lacking its previous punch. Further on, in years to come, the emollient hypocrisy of Major and Blair left less space for Class War’ fulminations against the clarion calls that were Thatcherism’s specialty. But Class War’s dead end as a political project only came fully home to me four years later when Bone and I, together with a thousand other people, attended Verso’s 25th anniversary party at the Porchester Hall in Notting Hill Gate.

Though the resources of Verso were always meager, we were determined to make a splash with the event. Waiters circled among the large crowd bearing trays of hors d’oeuvres and drinks and wearing T-shirts with an image of Che Guevara eating an ice cream from the cover of the Verso catalog that season. Big posters of Che were hung around the walls, flanked by large banners with the company logo.

I was on the stage listening to Christopher Hitchens, who I had just introduced, telling a joke about what would have happened if Khrushchev had been Lee Harvey Oswald’s victim in 1963 rather than JFK (to which the answer was that he thought it unlikely that Aristotle Onassis would have married Mrs. Khrushchev). Though not uncharacteristically boorish it was a good enough joke. But, boy, that was hard crowd to hold, too big and drunk to pay attention to an erratic sound system.

Then, at the back of the hall, hard to see because of the lights flooding the stage, I spotted a flailing of arms and a rapid clearing of space amongst the revelers. It was Bone, who was there with his wife. It later emerged that he had unilaterally launched a verbal barrage of such intensity and persistence towards Sheila Rowbotham and her companions that the diminutive and good-natured feminist historian had been driven to respond physically.

It was only then I fully realized that, unlike The Queen Mother, who Class War had once pictured smiling outside Clarence House under the caption “90 Years Old and Still Got Her Own Teeth … At the Moment,” Class War’s teeth had fallen out. The group had become victims of the slide from spontaneous crowd violence to individual acts of terror that so often afflicts anarchism.

In that sense Sinclair’s LRB piece was right. But when, as I occasionally do, I flick back through the pages of the book, reflecting on the awful years of Thatcher’s Britain, it seems to me that Class War’s howls of incandescent rage were, for a period, all there was. It wasn’t much, but it at least kept the idea of some sort of radical hope alive. At the end of the “Decade of Disorder” an economic boom and the focus groups of New Labour changed the tone of politics quite markedly. The poor became poorer still, and the rich much richer, but people weren’t so angry about it anymore. I don’t think Class War can be blamed for that.

Colin Robinson is Co-Publisher of OR Books